The members of John Wesley United Methodist Church in historic downtown Lewisburg are like a family.

They laugh as they reminisce about Mrs. Cabell, an old teacher and church organist who would spy on them from the pipe organ’s mirror, then call them out at school come Monday morning for misbehaving in the pews.

They smile as they talk about how their “exchanging the peace” tradition — the hugging and greeting they did with one another and with any visitor during pre-Covid worship service — was a hard habit to break when the pandemic hit.

They shake their heads as they remember the days when they and the other kids from their old neighborhood, Gospel Hill, knew they’d better be back on their own side of town by 10 p.m., and that they could buy a hot meal in a brown paper sack — if they knew the right white people to meet at the back doors of the downtown restaurants just around the corner from their church.

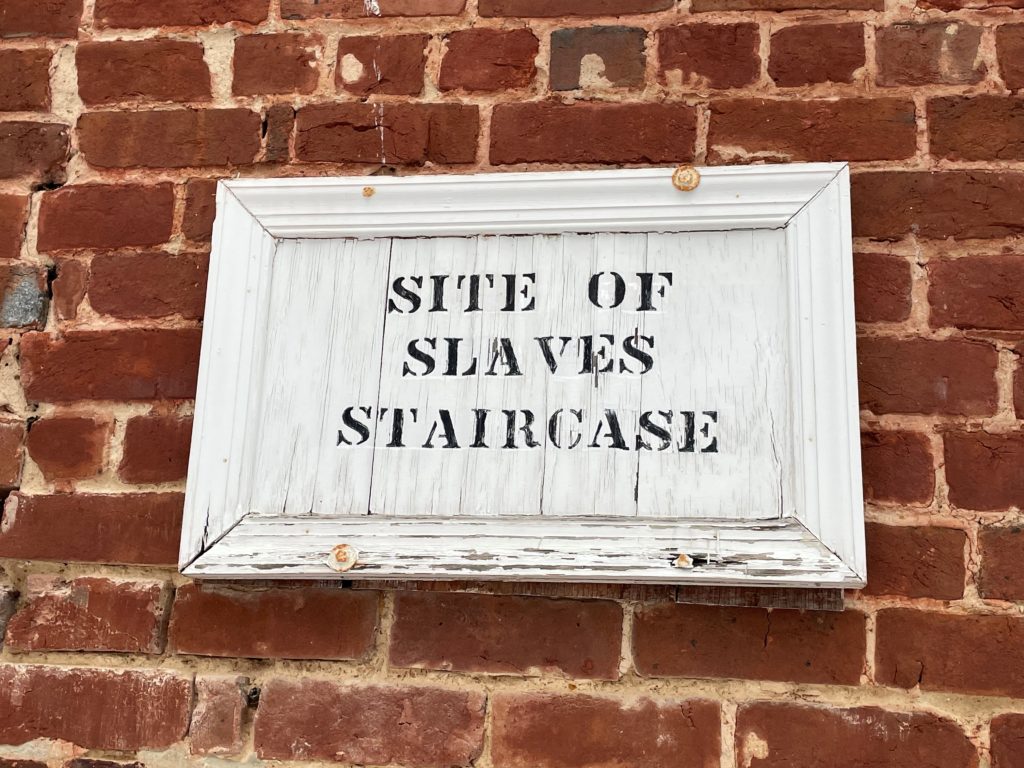

They speak with a mixed sense of pride and horror as they point out what used to be a steep outdoor stairway, a slave entrance leading up to the gallery where some of today’s members imagine their ancestors may have learned many of the very same hymns their musically gifted choir leads today.

They sit on the same curved pews where the owners of those ancestors sang about love and grace, just on the other side of a church entry people of their color weren’t even allowed to use.

(Center) Though John Wesley UMC rarely uses its balcony for worship services, benches such as these remain. Some members say they sense the presence of the saints who once sat on them.

(Right) A view of the sanctuary from the balcony.

They tap their feet on 201-year-old creaky, narrow floorboards. If those boards could talk — and some believe they can, in a way — it might tell a story that no one walking on them today can even begin to understand. It’s a story where somehow, in the worst of circumstances, grace floated up into a slave gallery and planted a seed that grew generation after generation, so deeply rooted that not even a Civil War cannonball could shake its foundation.

“We know from whence we came, and we can look back. Sometimes we can even feel that presence,” says Sandra Wilmer, a trustee and chair of the church administrative council. “But to me, God is who brought us this far, and that makes it all worthwhile.”

If they look back far enough, they read of Bishop Francis Asbury, Methodist pioneer, holding conference in Lewisburg in 1771. Less than a decade later, the Methodists built a “church house” on what is now Foster Street. (At the time, it was German Street.) That building was later sold and converted into a dwelling local historians know as the McWhorter home.

By 1820, construction of the present building at 350 E. Foster Street began on donated property. Local masons burned bricks and joined them with clay mortar to form the Colonial-style structure with a cupola belfry on the roof.

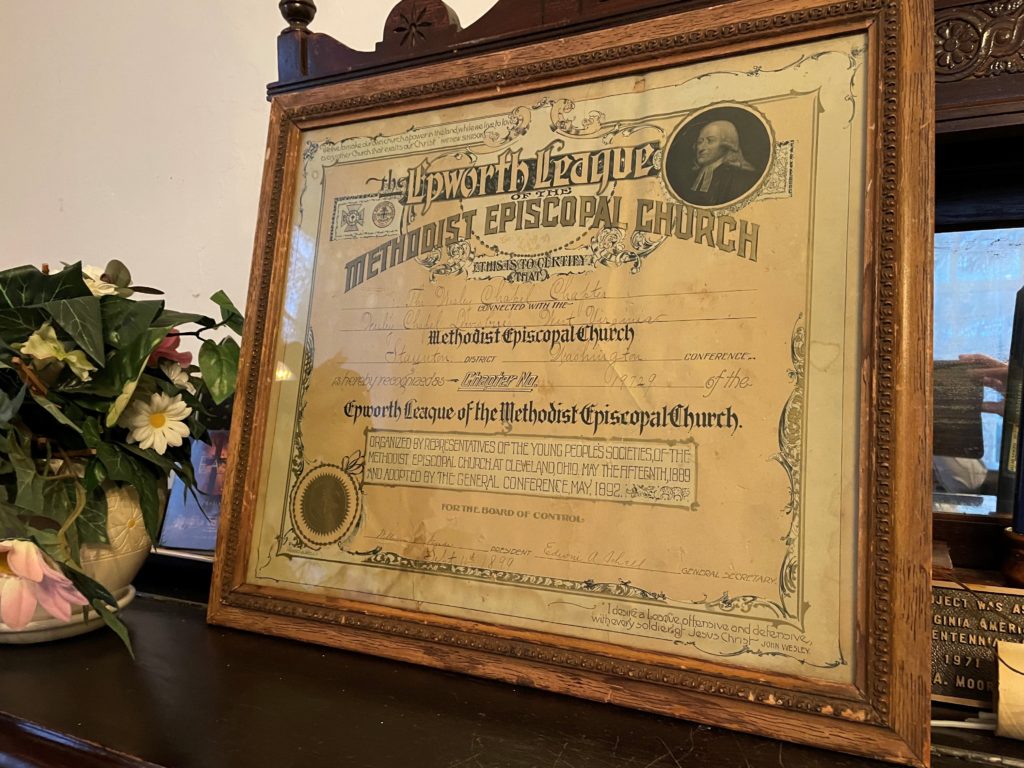

By 1828, though the structure stood firm, the larger church struggled, and a group withdrew from the Methodist Episcopal Church to form the Methodist Protestant Church. It wouldn’t be the last division. In 1844, the issue of slavery split the church again — this time into the Methodist Episcopal Church and the Methodist Episcopal Church, South. The church on Foster Street remained Methodist Episcopal, and a Methodist Episcopal, South church — which defended slavery — was built on Washington and Church Streets.

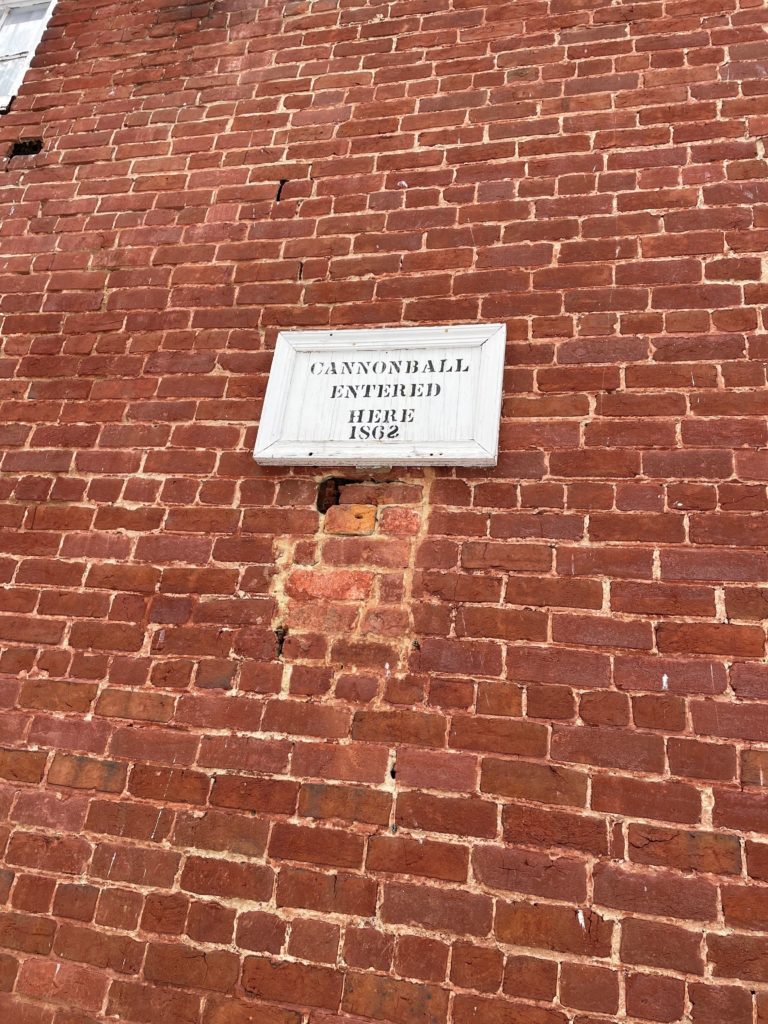

In May of 1862, Confederate troops were camped only a hundred yards east of John Wesley ME Church. On the morning of May 22, Union forces began to shell the Confederate camp. History explains that a Union gun broke from its support and missed its target. Instead, it hit the church, which was being used as a hospital. Scars remain.

(Right) Mike Burns, incoming trustee chair, holds the Civil War cannonball that hit John Wesley UMC in 1862. Visitors to the church are welcome to examine it through a glass display case that houses other church memorabilia.

By 1939 — when the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, the Methodist Protestant Church, and the Methodist Episcopal Church united to form the Methodist Church — segregation still loomed in the form of a separate Central Jurisdiction for black conferences. But in April of 1968, in Dallas, Texas, that changed. The Methodist church united with the Evangelical United Brethren to form the United Methodist Church, without a separate jurisdiction for black churches.

By 1974, all traditionally black conferences had merged with regional conferences, and it was around that time that members of John Wesley UMC began a church restoration project, embracing their heritage and history with financial assistance from the West Virginia Antiquities Committee.

“When I think about 200 years ago, when I look at the stonework, the construction, it is beautiful,” says Mike Burns, incoming chair of the church’s trustees.

He admits a 201-year-old building — even one that underwent some restoration in the 1970s and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places — comes with its fair share of physical problems.

“But the material that was used when they built it — some of it you can’t even get today,” he says in awe. “These are materials that outlast anything that we’re using today. It’s the reason this church has been standing so long and in such good condition. But there are things in need of repair. Things we are working toward to get the job done. …

“The spirit is here from our ancestors to us and hopefully going forward,” Burns says. “It’s a blessing to be able to say our doors are still open.”

“Everybody in here wears triple hats,” adds Wilmer. “That’s the way it’s been since we were kids. People just appreciated and honored the church grounds.”

And they appreciated and honored each other.

“When I came through those front doors, even as a child, I could always feel the spirit of this church, like God was in here,” says Beverly White, a trustee and lay leader. “It is hallowed ground.”

It’s one of the things Wilmer missed during the decades she lived in another state.

“I never found another church that could match the feeling I get when I walk in those doors,” she said.

That feeling may have something to do with the historic building and the spirits of the past they say they can often feel, but it’s more than that.

“It’s the people,” says Rosalyn Lee, outgoing chair of the trustees. “It’s the people who make the church. And there’s no criticism here. Just the love.”

“And maybe the food,” she adds, laughing.

Pastor Eugene Fullen agrees.

“When I first came here, I was received with the love that we’ve been talking about,” Fullen says, noting that his own skin is not the same color as many of those with whom he worships. “ … My wife and I became a part of this very sacred place. There is a pain here that they can feel, that I can’t feel in the same way. But we can all see the love and the teaching that was done in this church. We really do have this open doors, open hearts, open minds policy, and I don’t have to preach that. It was here when I got here.”

(Right) Standing in front of the curved pews in the sanctuary of John Wesley UMC are, from left, Trustee Mike Burns, Trustee Rosalyn Lee, Pastor Eugene Fullen, and Administrative Council Chair Sandra Wilmer.

“We know what it feels like to be discriminated against,” Lee says, “and we would never want anyone to feel that way.”

“African, white, women, men, Indian, everybody.” Wilmer says. “They are welcome here, and they come here. We have open minds, open hearts, and we live that creed every day.”

As they recall their own history, growing up in the 1960s, they do so with affection for their church and friends, and sadness for the racism that was a part of their reality.

“Those people who were cruel to us, their children and our children are the best of friends, so they learn,” Lee says. “It was like that. There was discrimination. But this community has grown, learned, seen, evolved. And we continue learning. Every day I learn something new, and I’m 68.”

As far as they’ve come, this church family recognizes growth is still necessary, outside their doors and within them. Like other congregations, they are concerned about the lack of young adults in church, and they are concerned about their community — one that, despite its small town charm, still lacks black-owned businesses and offers few job opportunities for their grandchildren.

“Yes, there is this ancestral thing. Slavery,” Lee said. “And they had a day of rest and a day of worship. God was your way out of the trying times that you had. God, education. And this was the meeting place. This was the teaching that they had, that we have to show us how to live our lives with open minds, open hearts. And it has been ingrained in us through song, through actions, through worship.”