Featuring four WVUMC Bishops Representing 40 Years of service to the West Virginia Conference.

Though they gathered virtually, four bishops who have served the West Virginia Conference in the last 40 years recently sat down with Rev. Dr. Ken Ramsey for “Front Porch Conversations” about systemic racism.

In the new three-part series available for online viewing and small group study, the bishops and host Ramsey, who serves as senior pastor at Bridgeport United Methodist Church, offer personal testimony, celebrations of progress, signs of hope, and a call to follow Jesus by working toward racial and ethnic equality.

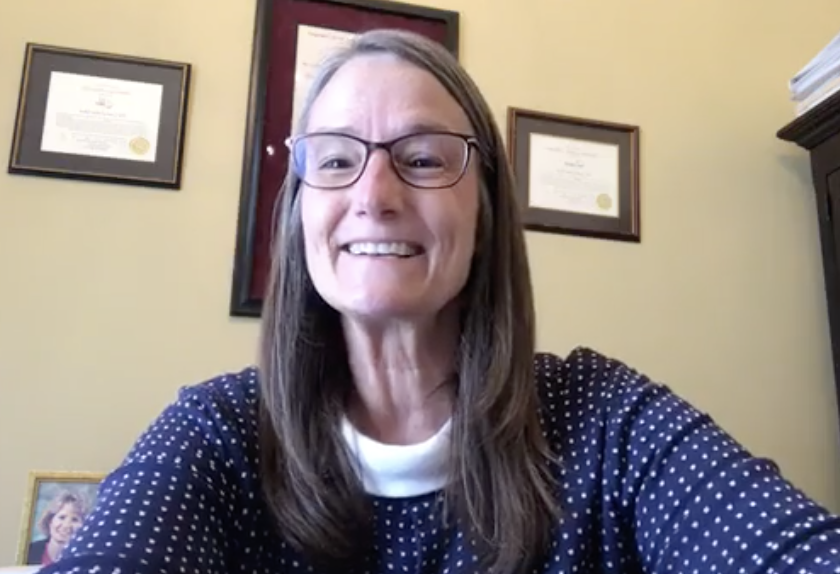

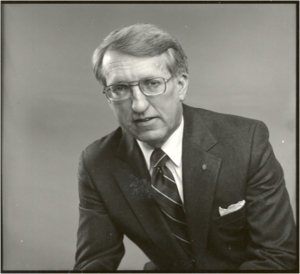

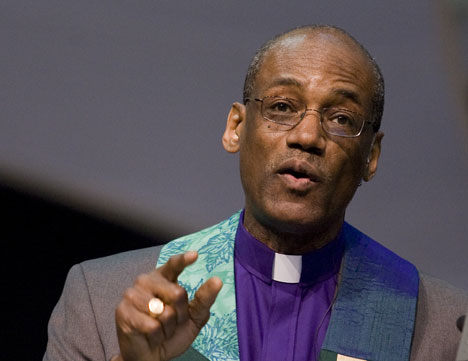

Ramsey is joined on the virtual front porch by Bishops William Boyd Grove (1980-92 and 2011-12), Cliff Ives (1992-2004), Ernest Lyght (2004-2011), and Sandra Steiner Ball (2012-present).

“What this process will help all of us to do is to confront the matter of racism with honesty and integrity in a faithful effort to remove all the stains of racism that tarnish our nation and our beloved church,” says Lyght, the first African-American bishop to serve the West Virginia Conference.

Ramsey calls the porch discussions “an opportunity to engage more and explore more in what ways we might begin to make a real difference when it comes to addressing systemic racism.”

He starts the conversation by recalling a childhood memory from the State Fair of West Virginia in which an African-American boy his own age was made to wait while he was allowed to board a ride, even though the African-American child and his family were farther ahead in line.

“I remember thinking then, ‘Why was I allowed to go in front of them? Why did he have to wait?” Ramsey says. “Looking back, it’s a question that’s haunted me, because looking back, there are many times that I’ve been allowed to go in front of persons of color. They had to wait. Many are still waiting.”

For Steiner Ball, evidence of systemic racism presented itself recently, when she took a closer look at her own birth certificate. One of the information sections appeared to have been left blank. Upon further inspection, she discovered wording under the blank that said “Color, if other than white.”

“So, white was considered normal, expected,” she says. “(The state of Massachusettes was) making assumptions that is was okay and normal and privileged to be white, and that non-white was different and not the norm, and they needed to be identified.”

Grove discusses growing up in a time when he had no classmates or neighbors of color but parents who made an effort to form relationships with African-Americans, even joining the NAACP in the 1940s and inviting African-American friends for dinner.

“I discovered that black lives matter, and after they were gone (from dinner), my mother and dad talked to me and my two younger brothers about what racism is and … that there are a lot of people whose color is different. I remember my dad saying, ‘I wish you had some friends who were,’ — the word was then ‘colored.’ ”

Grove, who, as bishop, appointed a black pastor to a white church in Bluefield, also recalls his parents using the time after that dinner to explain how their Methodist faith called them to be anti-racist.

“That was the beginning of my struggle for the awareness of the reality of systemic racism,” he says. “When I was 13, I discovered what racism is. It took me 50 more years to know what white privilege is.”

That discovery became clear when a colleague of color explained the type of conversation he is forced to have with his teenage son, Grove continues. “He said, ‘Every day, when he goes out, I say to him pay attention, remember who you are and remember where you are. Don’t wear a hoodie. … At police stops, keep your hands on the wheel and say yes sir and yes ma’am. … How many of you have to say that to your teenage children?’ In that moment, I discovered what white privilege is.”

Ives, in the conversation, thanks Grove for bringing the anti-racist teachings of his parents and his church with him when he came to West Virginia, a place where he knew an elected African-American bishop once had not even been considered for assignment due to perceived attititudes about race.

“But I knew Grove had been working on the issue of racism,” Ives recalls of his early days of appointment to the West Virginia Conference. Around that same time, Ives also found himself on the board of directors on the General Commission on Religion and Race. He calls that appointment an answer to his prayers about being equipped to serve anywhere. In 2004, he would invite a United Methodist bishop of color to speak at Annual Conference in celebration of a four-year task force’s work focusing on racism in West Virginia.

“It seems ludicrous now to call that the conclusion of our work,” Ives says. “I’m proud of the work we did, but I know that wasn’t everything that needed to be done.”

Lyght, who made the trip from New Jersey to speak at the West Virginia Annual Conference to celebrate the culmination of Ives’ racism task force work, had no idea he would soon return as the state’s first African-American bishop. He recalls the warm welcome he received from West Virginia United Methodists.

“The West Virginia Conference is a gift to the entire United Methodist denomination,” Lyght says, recalling the common cultures of hospitality and theology he quickly discovered.

Steiner Ball agreed that West Virginia is “a wonderful place of hospitality.”

“But sometimes the hospitality is a thin veil covering the racism and the sexism that continue to permeate many of our communities,” she says, citing an ongoing need to raise awareness and build on diversity and inclusion.

Lyght, whose own rights were restricted by segregation laws, says he is thankful for this “new effort to dismantle and eliminate racism.”

“On my journey, there have been times when I have been a victim of racism,” he says, “but I confess that there have been instances when I have been complacent with the stain of racism by not speaking out. … We now live in the era of the Covid-19 pandemic and the racism pandemic. We have experienced the Black Lives Matter reality. The United Methodist Church has taught us that Black Lives Matter, as do all lives.”

Still, he says, there is work to be done.

“How can we design structures and opportunities that develop relationships, partnerships and friendships that overcome racism?” Lyght asks. “We are living in a time that confronts the United Methodist Church with many challenges. … I am reminded that challenges can provide opportunities for fresh beginnings. The racism challenge … is not new to the West Virginia conference. In a variety of ways the people of the West Virginia Conference have been grappling with this challenge for a number of years, and you have made progress.”

But the challenge remains, Ives notes.

“The current Black Lives Matter movement demands that white persons … not just understand but accept the fact of white privilege,” Ives says. “All of that calls us to the hard work of dismantling a system born in slavery and nurtured in segregation and broken awarenesses in our country.”

Grove says he is optimistic about an end to the injustice of racism.

“Forty years is a sacred story,” he says, referring to the years represented in the Porch Conversation, the Exodus story, and the words of Martin Luther King, Jr. “In one of his last speeches, he said, ‘I’ve been to the mountain and I’ve seen the promised land.’ … I won’t get there, but I can see it, and I think today we can say we may not get there. I may not get there, but I can see it. I can see it.”

A first step to getting there, Steiner Ball suggests, is reaffirming our baptisms.

“We need to remember who and whose we are and to hear God call our names once again,” she says, “to live as people who renounce evil. … We are all part of that one body, and no one person in the body is greater or lesser than any other part of that body. … Each person and each congregation can do something.”

Follow this link for the Front Porch Conversations page on the wvumc.org website.

Photos courtesy of Dewayne and Ginnie Lowther and WVUMC Staff. Special music on the videos recorded by Rev. David Johnston.